– (Reading Time: 17 mins Approx.)

NOTE TO READER: Read philosophically

RECAP: [While visiting the Indian museum Rose felt mesmerised hearing about the history of Indian Freedom struggle with context to Kolkata. As they were about to leave, they saw someone coming piercing the midnight fog in a horse carriage.]

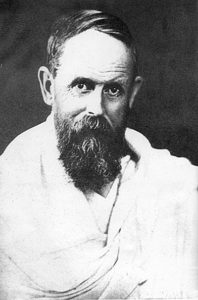

Hovering from the fog a black horse carriage stopped in front of us. A man in black coat, long beard stepped out of the horse carriage. Seeing him Sir Charles Stuart exclaimed in great joy – “Welcome Andrews! I am very happy to finally meet you.”

“Listen everyone, you all might have already heard of him. He is Charles Freer Andrews. Though he is very fond of me, but I personally admire him for his contributions and love for Calcutta.” – added Sir Stuart.

I could not believe my eyes. It was indeed Sir Charles Freer Andrews. A Christian missionary, educator and social reformer in India. I have heard a lot about him from Sir Stuart. Though he stays close to us (Charlie Andrews is buried in the ‘Christian Burial ground’ of Lower Circular Road cemetery, Calcutta) but we never really got the chance to meet him. Sir Stuart once promised me that if possible, he will make sure Sir Andrews comes to my death day party. We all were really glad that he could make it.

I could not believe my eyes. It was indeed Sir Charles Freer Andrews. A Christian missionary, educator and social reformer in India. I have heard a lot about him from Sir Stuart. Though he stays close to us (Charlie Andrews is buried in the ‘Christian Burial ground’ of Lower Circular Road cemetery, Calcutta) but we never really got the chance to meet him. Sir Stuart once promised me that if possible, he will make sure Sir Andrews comes to my death day party. We all were really glad that he could make it.

“Thank you for such a warm welcome. You must be Rose Aylmer? And if I am not mistaken this must be your Death day voyage in progress. I beg your pardon to arrive at the very last moment. I rarely get time these days. I have so much work in my hand for the welfare of this society that I hardly get time for myself even.” – said Sir Charles Freer Andrews.

“But India is a free country now. People of Calcutta are independent too. How come you are still under pressure of social reformation?” – asked sister Elizabeth.

“Well, my lady let me ask you a question then. What is independence to you?” – asked Sir Andrews.

“Being free, I think. Doing all that your heart wishes to do…” – confusingly replied sister Elizabeth.

“Do you think sleeping on the street can be someone’s wish?” – Sir Andrews asked with a calm face.

“What do you mean? I am sorry but I don’t understand…” – replied Elizabeth.

“When I see homeless people on the street, people butchering people in the name of religion, caste, and creed…I ask myself are we really independent? I haven’t done enough yet. I cannot forget what my beloved friend Tagore told me once – ‘Neither the colourless vagueness of cosmopolitanism, nor the fierce self-idolatry of nation-worship, is the goal of human history.’ Human have achieved freedom of knowledge, freedom to think, speak but considering the present times I see all of them taking all that struggle and sacrifices of great souls for granted. And I will not rest until the actual freedom is achieved by every living soul on this Earth.” – Sir Andrews eyes sparkled as he said all these words.

“When I see homeless people on the street, people butchering people in the name of religion, caste, and creed…I ask myself are we really independent? I haven’t done enough yet. I cannot forget what my beloved friend Tagore told me once – ‘Neither the colourless vagueness of cosmopolitanism, nor the fierce self-idolatry of nation-worship, is the goal of human history.’ Human have achieved freedom of knowledge, freedom to think, speak but considering the present times I see all of them taking all that struggle and sacrifices of great souls for granted. And I will not rest until the actual freedom is achieved by every living soul on this Earth.” – Sir Andrews eyes sparkled as he said all these words.

None of us could speak after his deep, thoughtful ideologies. We all started heading towards the cemetery bracing ourselves for Sir Andrews remarkable tales of history to come.

“I had been involved in the Christian Social Union since university and was interested in exploring the relationship between a commitment to the Gospel and a commitment to justice. I was attracted to struggles for justice throughout the British Empire, especially in India. I was mesmerised and overwhelmed to see the dedication of Indians towards their motherland.

In 1904 I joined the Cambridge Mission to Delhi and arrived there to teach philosophy at St. Stephen’s College. There I grew close to many of my Indian colleagues and students. Increasingly dismayed by the racist behaviour and treatment of Indians by some British officials and civilians, I strongly supported Indian political aspirations. I even wrote a letter in the Civil and Military Gazette in 1906 voicing these sentiments.” – said Sir Andrews.

In 1904 I joined the Cambridge Mission to Delhi and arrived there to teach philosophy at St. Stephen’s College. There I grew close to many of my Indian colleagues and students. Increasingly dismayed by the racist behaviour and treatment of Indians by some British officials and civilians, I strongly supported Indian political aspirations. I even wrote a letter in the Civil and Military Gazette in 1906 voicing these sentiments.” – said Sir Andrews.

He later became involved in the activities of the Indian National Congress and helped to resolve the 1913 cotton workers’ strike in Madras.

“I am sure you all were expecting from me to hear about the story of independence and its aftermath in Calcutta. I hope to meet your expectations well.” – smiled Sir Andrews.

The partition of India in 1947 was the division of British India into two independent dominion states, the Union of India and the Dominion of Pakistan. The partition involved the division of two provinces, Bengal and Punjab, based on district-wise non-Muslim or Muslim majorities. Also divided between the two new dominions were the British Indian Army, the Royal Indian Navy, the Indian Civil Service, the railways, and the central treasury. The partition was outlined in the Indian Independence Act 1947 and resulted in the dissolution of the British Raj, or Crown rule in India. The two self-governing countries of India and Pakistan legally came into existence at midnight on 14–15 August 1947.

The intense violence caused during the partition of India led to a shift in demographics in Bengal, and especially Kolkata; large numbers of Muslims left for East Pakistan, while hundreds of thousands of Hindus arrived to take their place. Kolkata received millions of refugees from what became East Pakistan without receiving substantial assistance from the central government.

Before the partition of India, Bengal went through a really dark time. It was the Bengal famine of 1943. An estimated 2.1–3 million, out of a population of 60.3 million, died of starvation, malaria, or other diseases aggravated by malnutrition, population displacement, unsanitary conditions and lack of health care. Millions were impoverished as the crisis overwhelmed large segments of the economy and catastrophically disrupted the social fabric. Eventually, families disintegrated; men sold their small farms and left home to look for work or to join the army, and women and children became homeless migrants, often travelling to Calcutta or another large city in search of organised relief. Historians have frequently characterised the famine as “man-made”, asserting that wartime colonial policies if the British created and then exacerbated the crisis.

Before the partition of India, Bengal went through a really dark time. It was the Bengal famine of 1943. An estimated 2.1–3 million, out of a population of 60.3 million, died of starvation, malaria, or other diseases aggravated by malnutrition, population displacement, unsanitary conditions and lack of health care. Millions were impoverished as the crisis overwhelmed large segments of the economy and catastrophically disrupted the social fabric. Eventually, families disintegrated; men sold their small farms and left home to look for work or to join the army, and women and children became homeless migrants, often travelling to Calcutta or another large city in search of organised relief. Historians have frequently characterised the famine as “man-made”, asserting that wartime colonial policies if the British created and then exacerbated the crisis.

Over the 1960s and 1970s, severe power shortages, strife in labour relations (including strikes by workers and lockouts by employers) and a militant Marxist-Maoist movement who sometimes used violence and property destruction as tactics of protest — the Naxalites — damaged much of the city’s infrastructure, leading to economic stagnation. (Ironically, this is the same city that has historically been a strong base of Indian communism: West Bengal was ruled by the Communist Party of India (Marxist) (CPI(M)) dominated Left Front for nearly three decades — the world’s longest-running democratically elected communist government.

Over the 1960s and 1970s, severe power shortages, strife in labour relations (including strikes by workers and lockouts by employers) and a militant Marxist-Maoist movement who sometimes used violence and property destruction as tactics of protest — the Naxalites — damaged much of the city’s infrastructure, leading to economic stagnation. (Ironically, this is the same city that has historically been a strong base of Indian communism: West Bengal was ruled by the Communist Party of India (Marxist) (CPI(M)) dominated Left Front for nearly three decades — the world’s longest-running democratically elected communist government.

In 1971, the war between India and Pakistan led to another massive influx of refugees from the former East Pakistan (now Bangladesh), and their settling in Calcutta massively strained its already damaged infrastructure.

“It was indeed the dark age for the people of Bengal. God knows, how many mothers lost their children, wives lost their husbands. There’s no pain in this entire universe that is bigger than the pain of losing a close one.” – Sister Elizabeth patted little Henry’s back in a soft manner.

We couldn’t help but think a city that has went through so much still manages to spread joy like the old times. Every morning a citizen wakes up with hope that yesterday might have been bad but today will be beautiful, better. “Hope” seems like a Magic Potion that drives Humanity.

Decades come and go but what remain are the impression and great acts of the social reformers. India is privileged to have number of great souls like Dayanand Saraswati and Raja Ram Mohan Roy. They managed to bring revolutions by making radical changes in the society. Some of the reformers took up the challenges of breaking the jinx of prevailing caste-system while some fought for the introduction of girls’ education and widow remarriage. The contributions, made by these, simple yet eminent souls towards humanity are really extraordinary. Their activities and thoughts guided the nation to a new beginning.” – concluded Sir Charles Freer Andrews.

Decades come and go but what remain are the impression and great acts of the social reformers. India is privileged to have number of great souls like Dayanand Saraswati and Raja Ram Mohan Roy. They managed to bring revolutions by making radical changes in the society. Some of the reformers took up the challenges of breaking the jinx of prevailing caste-system while some fought for the introduction of girls’ education and widow remarriage. The contributions, made by these, simple yet eminent souls towards humanity are really extraordinary. Their activities and thoughts guided the nation to a new beginning.” – concluded Sir Charles Freer Andrews.

I agree my kind left no effort to make your countrymen’s life miserable to the core and we all realise every single day how strong you all have been throughout the darkest hours of your country. And now when we see imposters and anti-socials trying to bring this country down in the name of politics, religion we feel bad. Because it has been decades your city has given us shelter here. We think of it as our own. I am sad that I will never be able to lie down on the soil of England, but I am proud that my remains will forever stay in a country of great historical, cultural as well as spiritual importance.

We finally reached our home. The sunrise was about to peek out from the night sky. People are soon to wake up from their deep sleep. And we are soon to return back to our consecutive graves. Little Henry slept like an angel all this time, which eventually gave us the time to cherish a peaceful tour of this city. “I am facing scarcity of words to pay me regards to you all for making this night so special. Thank you, Sir William Jones, for your guidance. I am grateful to you Colonel Robert Kyd for taking us all to the Indian Botanic Garden. How can I ever repay your love and care sister Elizabeth! The trip would have been much boring if you weren’t with us Captain Thomas Cooke. Without you Sir Charles Stuart, we all have been ignorant to the glorifying history of The City of Joy. And I cannot be more grateful to make time and join us Sir Charles Freer Andrews.” – I said.

Everyone smiled and greeted me for another time. We all promised to meet again. In the end, the only thing I, Rose Aylmer want to say to you all, that – “Come forward and protect your beautiful city from every darkness of man-made destruction. Living Deads of the Park Street Cemetery will remain beside you forever. Reiterating the glorious tales of your astonishing past.”