The Subtle Touch

— by Mr. Ashoke Viswanathan

— Reading Time – 7 min Approx

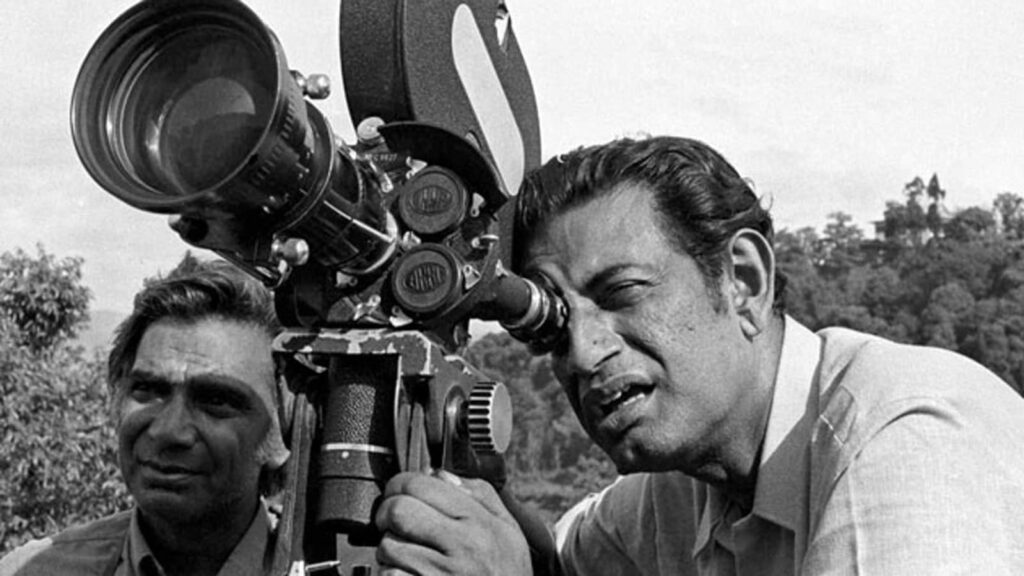

That Satyajit Ray is a wonderful storyteller, has been written about; but the fact that he often subverts his narratives is often overlooked. The majority of his films are replete with instances of how, in an exceedingly subtle manner, he has moved away from the linear track and adopted the discursive mode.

Consider the basic text of SHATRANJ KE KHILADI (1978), a film that is often grossly underrated. The essential structure of both the Premchand text (on which it is based) and the film screenplay is hydra-headed.

There are more than one parallel narratives for one; then again, the one story seems a microcosm of another strand. Besides, there is a hint of magic realism in the visualization of the chess board with all the pieces including knights and rooks and pawns eventually giving way to the inexorable ‘March of the British army in Awadh’, replete with horses, elephants and soldiers!

The director’s deft touches are not restricted to merely designing the structure of the narrative. Within the parallel strands, too, he has presented situations that are revealing of character and motive. General Outram is a magnificent creation, not etched purely in dark shades but drawn with great generosity of spirit; he is full of the prejudices of a British officer scrutinizing the questionable administrative abilities of an Indian monarch but the way he is played by the redoubtable Sir Richard Attenborough makes the obviously negative import of the officer’s actions more a matter of Imperial policy than any hatred for the so-called king, more interested in art and culture than useful governance.

The discursive pattern recurs in the dialogue sequences between Outram and Weston (played by Tom Alter) wherein it is not just the background of Wajid Ali Shah that is being revealed but, more, the attitudes of the two officers. Outram is fond of Weston who has a remarkable command over the Hindustani language (Urdu) but warns him, all the same, that any admiration he may have for Wajid Ali Shah may, in the long run prove to be detrimental to his prospects of a promotion in the British army.

The interactions between Mirza Sajjad Ali and Mir Roshan Ali (The chess players) are full of subtle nuances. Mir Roshan Ali is a beautiful creation, full of mischief and is not averse to changing the pieces when Mirza is not in the room. Saeed Jaffrey plays the character with aplomb, bringing out the right amount of dismay and shame while realizing that he has been cuckolded.

One scene stands out. When Mirza and Mir visit Abajani, the ailing lawyer, with a view towards borrowing his chessboard and pieces, the scene becomes a trope for the stasis enveloping Lucknow as also the insensitivity of the chess players in a region that is about to witness an abrupt change of power.

ARANYER DIN RATRI (Days and Nights in the forest – 1969) is another film that has not been analysed or discussed with the same enthusiasm as the other films of Ray; albeit it is true that in the West, the film was received with a surfeit of applause. In fact, the renowned film critics, Pauline Kael praised the film to the skies at the Berlin Film Festival where it was shown in the Competition Section.

This film, too, has a unique structure and a novel pattern in its dramaturgy. It begins like a ‘road film’ but its structure is that of a linear narrative. The travels and travails of the four friends are chronicled

with generous doses of wit and humour; their interactions with the three women are described with great spontaneity. Gradually the structure of the text becomes syntagmatic with four parallel strands emerging out of the initial story: Ashim and Aparna come close, but a plethora of doubts prevail; Sanjoy is taken up with Jaya; Hari is involved in an erotic rendezvous with Dhuli; and Sankar is busy gambling. In each of these tracks, Ray uses the subtlest of constructs to convey meaning.

The sand slipping through Aparna’s hands is an exquisite symbol of time. It is also reminiscent of the memory game that Aparna deliberately lost to Ashim! Sanjoy’s running away from Jaya is a comment on the quintessential Bengali ‘gentleman’. And Hari getting beaten up is a kind of cinematic equivalent of ‘divine justice’, the seeds for which were sown when the four friends were unfair to the ‘help’ at the Rest House.

Through the sequence comprising several scenes, the soundtrack is rich with the sounds of the Santhal drums and their songs. The complete effect is hypnotic; it is as if a masterpiece of an art- installation has combined the sights and sounds to create a mesmeric effect on the viewer.

This film is in the Palamau district of Bihar, but Kolkata (then Calcutta) is very much present. Even in the rural milieu, so close to the forest, the attitudes of people from the big city draw attention and makes one wonder whether or not the environment is a crucial factor in forging relationships.

Ray is masterly in his dramaturgy. The dialogue meanders, ever so slightly, to create debate, drama and conflict in the interaction between Ashim and Aparna.

There are the faint stirrings of a relationship and yet, there is ego, there is middle-class morality and there is the fear of overstepping, of crossing the line. All this comes in between.

Often deviating from the Sunil Gangopadhyay story on which the film is based, Ray introduces small mannerisms and characteristics in his supporting cast. The face of authority is to be feared and obeyed but here, the person concerned has a stammer. Sankar is overtly comic, but he is more of an ordinary young man without a care in the world. Rabi Ghosh essays the role effortlessly and some of his dialogues and gestures are richly resonant.

In all his films, Ray has actors who are so believable. They don’t seem to be acting at all. Harihar and Sarbojaya from ‘Pather Panchali’, Soumitra Chattopadhyay and Sharmila Tagore from ‘Apur Sansar’, Tulsi Chakraborty from ‘Parash Pather’, Madhavi Mukhopadhyay from ‘Charulata’. The list is endless.

If his creation of memorable characters was a factor in his films achieving a kind of immortality, then his understanding of the fact that sound needs to have an equal contribution with the image is surely another factor in his presentation of the audio-visual experience. Who can forget the application of Raag Patdeep on the Taar-shehnai in the scene when Harihar finally returns only to find that Durga is no more.

Sarbojaya’s howls are replaced by the instrument wailing on behalf of the human voice: it is a frighteningly tragic scene where the sound seems to take over the mantle of the signifier.

In the dream sequences in NAYAK (The Hero-1966), the sound design is noteworthy owing to its creativity, often bordering on the bizarre. Although the concept of a successful hero sinking into a quicksand of cash may seem a little heavy handed – even obvious and unsubtle – the soundtrack is interesting to say the least. The sounds of the many telephones and their abrupt and sudden ringing generates an atmosphere of suffocation and anxiety that is very appropriate. Add to this the traditional invocation of the God, Hari, when pall bearers bear the dead body to the crematorium – and the effect is truly disturbing.

Ray is known for his minimalism. In his sound design, too, he works at a subterranean level adding sounds that are often highly connotative. If Charu’s use of the lorgnette in CHARULATA (1964) is an ideal visual index particularly when she applies it on her own husband, then the recurrence of the ‘monkey-man’s’ sound just as the husband turns to go down is a poignant reminder of Charu’s predicament wherein even her husband has become as unattainable as the outside world.

Elsewhere in the film, when his own brother-in-law is about to decamp with much of his funds, Bhupathi and his cronies are celebrating the victory of the Liberals over the Tories in England by having a friend sing a song written by Raja Rammohan Roy. This piece of diegetic sound becomes non dietetic as it is overlapped on an extremely anxious Amal who is guilt – ridden for having encouraged the extra-marital intimacy that Charu has gradually been drawn into. The song becomes a sombre dirge as Bhupathi is betrayed on two counts by two relatives.

In conclusion, it is quite obvious that Ray, in various ways, visually and aurally, is able to add texture to his narrative. This he does gently, in an unnoticed manner. In his mise-en-scene, particularly, he is able to add elements of arresting framing, eloquent camera movements, creative decoupage and exquisite camera-character choreography to present sequences of great artistic merit.

In Pratidwandi (The adversary – 1971), the protagonist, Siddhartha, in a final outburst of pent-up frustration overturns the table in the interview room. The camera tracks with him as he storms out. Then a series of moving shots of the metropolis reveals its scarred visage replete with political graffiti until one moves out of the city and sees the protagonist in the countryside travelling to take up a job in a semi-rural milieu. This sequence, so succinctly presented, seems a searing critique of a decaying system and is achieved in one fell swoop.

Ray is truly the master of understatement.

-by Abhrajita Mondal

Dear Reader, Hope you liked the post. If you think our initiative “The Creative Post” is worth supporting, then please support us by paying the amount you think we are worthy of. We believe, the value of content should be decided by the consumer. Hence we request you to evaluate our worth and pay accordingly by Clicking Here.