— by Aritri Chatterjee

–Reading Time – 24 min Approx

Chinamma didn’t listen to Sunetra at all. She arranged a car to drop her at Kulithalai, Tamil Nadu. Somehow, Sunetra is falling in love with road trips rather than the comfort of flights. There’s nothing more breathtaking than entering an unknown territory by witnessing its nature and people. The roads give so many experiences and memory whereas being among the clouds takes away the chance of knowing the unknown.

Sunetra looked at her watch. Kulithalai is not very far from Kerala. It is going to be an approx. 6 hours drive. She is going to visit a very prestigious Bharatnatyam school there; named Kalai maṟṟum paṭaippāṟṟal (Centre for Art & Creativity). She already had breakfast at Chinamma’s house before leaving. Chinamma cared for her like a mother. The car should be reaching Kulithalai by 1 p.m. Kulithalai has important historical backgrounds that can’t be ignored.

Kulithalai is a town in Karur district in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu. The recorded history of Kulithalai is known from Cheras, followed by medieval Chola period of the 9th century. It has been ruled, at different times, by the Medieval Cholas, later Cholas, Pandyas, Vijayanagar Empire and then the British. The town derives its name from the presiding deity of the Kadamba Vaneswarar temple. The 7th century Nayanmars (Saiva saints) Thirunavukkarasar, revered the place as Kadambandurai and Kuzhithandalai in his works in Tevaram. The word Kuzhithandalai, in modern times, is denoted as Kulithalai. As per Hindu legend, Saptha Matha, the seven divine virgins were praying to god Shiva in the Kadamba forest located here to save them from a demon named Doomralochana. Shiva is believed to have killed the demon to save the forest and the virgins, thereby getting the name Kadambavana Vaneswarar, meaning the Lord of Kadamba Forest.

India’s history is fascinating, Sunetra thought to herself. She decided to gather as much information as she can before reaching Kulithalai on Bharatanatyam. Chinamma gave her a book on this eloquent dance form. She opened and started reading it.

The theoretical foundations of Bharatanatyam are found in Natya Shastra, the ancient Hindu text of performance arts.Natya Shastra is attributed to the ancient scholar Bharata Muni, and its first complete compilation is dated to between 200 BCE and 200 CE, but estimates vary between 500 BCE and 500 CE. The most studied version of the Natya Shastra text consists of about 6000 verses structured into 36 chapters. The text describes the theory of Tāṇḍava dance (Shiva), the theory of rasa, of bhāva, expression, gestures, acting techniques, basic steps, standing postures—all of which are part of Indian classical dances. Dance and performance arts, states this ancient text, are a form of expression of spiritual ideas, virtues and the essence of scriptures.

More direct historical references to Bharatnatyam is found in the Tamil epics Silappatikaram (c. 2nd century CE) and Manimegalai (c. 6th century). The ancient text Silappatikaram, includes a story of a dancing girl named Madhavi; it describes the dance training regimen called Arangatrau Kathai of Madhavi in verses 113 through 159. The carvings in Kanchipuram’s Shiva temple that have been dated to 6th to 9th century CE suggest Bharatanatyam was a well-developed performance art by about the mid-1st millennium CE.

A famous example of illustrative sculpture is in the southern gateway of the Chidambaram temple (12th century) dedicated to the Hindu God Shiva, where 108 poses of the Bharatnatyam, that are also described as karanas in the Natya Shastra, are carved in stone.

Bharata Natyam is traditionally a team performance art that consists of a solo dancer, accompanied by musicians and one or more singers. The theory behind the musical notes, vocal performance and the dance movement trace back to the ancient Natya Shastra, and many Sanskrit and Tamil texts such as the Abhinaya Darpana.

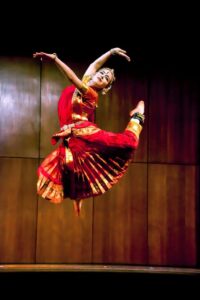

The solo artist (ekaharya) in Bharatanatyam is dressed in a colorful Sari, adorned with jewelry who presents a dance synchronized with Indian classical music. Her hand and facial gestures are codified sign language that recite a legend, spiritual ideas or a religious prayer derived from Hindu Vedic scriptures, the Mahabharata, the Ramayana, the Puranas and historic drama texts. The dancer deploys turns or specific body movements to mark punctuations in the story or the entry of a different character in the play or legend being acted out through dance (Abhinaya). The footwork, body language, postures, musical notes, the tones of the vocalist, aesthetics and costumes integrate to express and communicate the underlying text.

In modern adaptations, Bharatanatyam dance troupes may involve many dancers who play specific characters in a story, creatively choreographed to ease the interpretation and expand the experience by the audience.

“We are about to reach Kulithalai in half hour madam. If you want, I can stop on food station for lunch.” – the driver said to Sunetra. She got drowned in the book and his voice pulled her back. Sunetra realized that it’s 12 p.m now and she does feel a bit hungry. She also wanted to explore the cuisine of Tamil Nadu. “Please stop somewhere. I do feel hungry. We both will have lunch there. And after dropping me in Kulithalai you can return back. I am highly grateful to you all for making this journey memorable for me.” – Sunetra said with a smile. Driver Santoshji smiled back and said – “You’re very humble madam. May God grant all your wishes. You are very strong. People who surrender in front of difficulties should admire your courage and learn from it.” Sunetra’s heart got filled with positivity. The world would’ve been so much better if we all could appreciate each other for what we are.

They stopped near a hotel. A little boy came out seeing the car. “Come in. We are the best taste of South India.” – the little boy said with bright eyes. Sunetra smiled and pressed his chick softly. “We would like to have lunch. What are your specialties?” – she asked. The boy took them inside and gestured to a table nearby to take their seat.

As they sat down, a man with a big smile on his face came towards them. “Welcome to Tamil Nadu! My name is Prajapati Poriya. This is my hotel and that’s my son, swami.” – the man said. Sunetra smiled back and said – “Thank you for your hospitality. We would like to have lunch here. I would love to have some authentic Tamil food.” Mr. Prajapati gestured a boy and told them the food will be there in a minute. The hotel was clean and neat. There were 6-7 people eating there.

A man came and placed banana leaf in front of them and started serving the dishes one by one upon the leaf. After he left Sunetra was surprised looking at her meal; it was filled with various recipes. She couldn’t understand what is what and from where to start. Detecting her confusion, Mr. Parajapati came and said – “Would you like me to give you a tour about this dish?” Sunetra embarrassingly smiled and nodded her head.

“This is Tamil cuisine in its authentic form. It was first originated by the Iyengars or Tamil Brahmins who decided to remain true to their roots. It originated from the ritual of Annadana, a custom of serving food to God and then distributing it to the people in Tamil temples. The meal is pure vegetarian fare served on banana leaves and is called Ilai Sappadu. ‘Sappadu‘ means a full course meal that accommodates all the six tastes – sweet, sour, bitter, salty, pungent and astringent. It consists of a never-ending array of dishes such as Poriyal (Fried or Sautéed Vegetables), Rice, Varuval, Pachadi, Idli, Payasam, Sambar, Thokku, Vadai, Kuzambu amongst others.” Sunetra got more and more overwhelmed listing to all this.

A boy came and placed a bowl of fish curry in front of them. Mr. Prajapati said – “This is another specialty of my hotel. The name of this dish is ‘Meen Kozhambu’. A Kozhambu recipe to rule them all. Kozhambu is a gravy preparation with a base of tamarind, toor dal and urad dal(grains). This one is a fish curry is made with whole of chilies and tamarind that makes it hot and sour in one bite. Please enjoy!” Mr. Prajapati paid his regards with the gesture of ‘Namaskar’ and left towards the kitchen.

Sunetra filled her mouth with the delicacies of south India. Santoshji was also eating happily. She was planning the journey afterwards in her mind just when a middle-aged man came towards her. “Excuse me for disturbing you in the middle of your meal but are you Sunetra Tripathi?” – the man asked with a curious face. Sunetra got surprised and said – “Yes, but how do you know my name?”

“Let me introduce myself. I am Paresh Mitra. I am researching on ‘Change of traditions in Indian Classical Dances’. I live in Bangalore but I am going to the Centre for Art & Creativity (C.A.C) to conduct a seminar for their students. I visited Mumbai once and was present at your last show.” – his face deemed down a bit while he uttered the last sentence. I think, your gesture and dedication to Kathak was commendable. It’s my pleasure to meet you.” – the man smiled and said.

Sunetra’s heart ached a bit as Mr. Mitra reminded her of the last show of her life. Somehow, she pulled back herself and smiled at him. “So, kind of you. Actually, I am also going to C.A.C. I wanted to meet them for my blog on Bharatanatyam. I was just going to leave after finishing the meal.”- Sunetra said. “Then we can go together if you won’t mind. Bharatnatyam has been my special area of research.” – Mr. Mitra replied.

After finishing their meal Sunetra got into Mr. Mitra’s car to head to C.A.C. Santoshji blessed her and left for Kerala. Mr. Mitra started answering Sunetra’s all question that she began asking about Bharatanatyam.

The repertoire of Bharatanatyam, like all major classical Indian dance forms, follows the three categories of performance in the Natya Shastra. These are Nritta (Nirutham), Nritya (Niruthiyam) and Natya (Natyam).

- The Nritta performance is abstract,

fast and rhythmic aspect of the dance. The viewer is presented with pure movement in Bharatanatyam, wherein the emphasis is the beauty in motion, form, speed, range and pattern.

fast and rhythmic aspect of the dance. The viewer is presented with pure movement in Bharatanatyam, wherein the emphasis is the beauty in motion, form, speed, range and pattern. - The Nritya is slower and expressive aspect of the dance that attempts to communicate feelings, storyline particularly with spiritual themes in Hindu dance traditions.

- The Natyam is a play, typically a team performance, but can be acted out by a solo performer where the dancer uses certain standardized body movements to indicate a new character in the underlying story.

Bharatanatyam, like all classical dances of India, is steeped in symbolism, both in its abhinaya (acting) and its goals. The roots of abhinaya appear in the Natyashastra text, which defines drama as something that aesthetically arouses joy in the spectator, through the medium of actor’s art of communication, that helps connect and transport the individual into a sensual inner state of being.

A performance art, asserts Natyashastra, connects the artists and the audience through abhinaya (literally, “carrying to the spectators”), that is applying body-speech-mind and scene, wherein the actors communicate to the audience, through song and music. Drama in this ancient Sanskrit text, thus is an art that engages every aspect of life to glorify and give a state of joyful consciousness.

The communication through symbols is in the form of expressive gestures and pantomime set to music. The gestures and facial expressions convey the Ras (sentiment, emotional taste) and bhava (mood) of the underlying story. In the Hindu texts on dance, the dancer successfully expresses the spiritual ideas by paying attention to four aspects of a performance: Angika (gestures and body language), Vachika (song, recitation, music and rhythm), Aharya (stage setting, costume, make up, jewelry), and Sattvika (artist’s mental disposition and emotional connection with the story and audience, wherein the artist’s inner and outer state resonates). Abhinaya draws out the bhava (mood, psychological states).

The gestures used in Bharatanatyam are called Hasta (or mudras). These symbols are of three types: Asamyuta Hastas (single hand gestures), Samyuta Hastas (two hand gestures) and Nritta Hastas (dance hand gestures). Like words in a glossary, these gestures are presented in the Nritta as a list or embellishment to a prelim performance. In nritya stage of Bharatanatyam, these symbols set in a certain sequence become sentences with meaning, with emotions expressed through facial expressions and other aspects of abhinaya.

Bharatanatyam contains at least 20 asanas found in modern yoga, including Dhanurasana (the bow, a back-arch); Chakrasana (the wheel, a standing back-arch); Vrikshasana (the tree, a standing pose); and Natarajasana, the pose of dancing Shiva. 108 karanas of classical temple dance are represented in temple statuary; they depict the devadasi temple dancers who made use of yoga asanas in their dancing.[88] Bharatanatyam is also considered a form of Bhakti Yoga. However, Natarajasana is not found in any medieval hatha yoga text; it was among the many asanas introduced into modern yoga by Krishnamacharya in the early 20th century.

Bharatanatyam rapidly expanded after India gained freedom from the British rule in 1947. It is now the most popular classical Indian dance style in India, enjoys high degree of support in expatriate Indian communities, and is considered to be synonymous with Indian dance by many foreigners unaware of the diversity of dances and performance arts in Indian culture. In the second half of the 20th century, Bharatanatyam has been to Indian dance tradition what ballet has been in the West.

When the British tried to attempt to banish Bharatanatyam traditions, it went on and revived by moving outside the Hindu temple and religious ideas. However, post-independence, with rising interest in its history, the ancient traditions, the invocation rituals and the spiritual expressive part of the dance has returned.[90] Many innovations and developments in modern Bharatanatyam, states Anne-Marie Geston, are of a quasi-religious type.[90] Major cities in India now have numerous schools that offer lessons in Bharatanatyam, and these cities host hundreds of shows every year.

Outside India, Bharatanatyam is a sought after and studied dance, states Meduri, in academic institutes in the United States, Europe, Canada, Australia, Sri Lanka, Malaysia and Singapore. For expat Indian and Tamil communities in many countries, it is a source and means for social life and community bonding. Contemporary Bharatanatyam choreographies include both male and female dancers.

In 2020, an estimated 10,000 dancers got together in Chennai, India, to break the world record for the largest Bharatanatyam performance. The previous record of 7,190 dancers was set in Chidambaram in 2019.

Sunetra didn’t realize when they reached Kalai maṟṟum paṭaippāṟṟal (Centre for Art & Creativity). Mr. Maitra gestured her towards the office premise and said- “Come let me introduce you to all the honorary people here. After the seminar I am sure you will be more overwhelmed. There are going to be some solo performances and demonstration as well. I hope you will enjoy.” Sunetra followed Mr. Mitra as if, she is walking towards her long-waited wish, that is soon to become reality.

— by Aritri Chatterjee