– (Reading Time: 25 min Approx)

Sunetra was standing near the Athirapally waterfalls. She thought to herself, there is so much to life when you decide to fight back. Sunetra came to Thrissur this morning. Last night she took a bus from Trivandrum. Vanumati herself came to drop Sunetra to Trivandrum Bus Stop all the way from Kovalam beach. Sunetra will remember her forever, her eyes sparkled in tears of joy while bidding goodbye to Vanumati.

In three days, they became friends, perhaps for entire lifetime. Dance connected their souls like nothing could have. Sunetra took pictures of herself standing near the waterfall. She noticed a group of people were staring at her amputated leg. She rolled up her jeans to avoid getting wet because of the waterfall, thus it can be visible. If it was any other time Sunetra might have felt embarrassed but now she doesn’t care. The people might sympathise for her condition which she respects from heart; but if only they could know how free she feels now! She again said to herself, “There is so much to life when you decide to fight back!”

Thrissur holds an important place when it comes to the prestigious heritage of the dance forms of Kerala. In a small town of Cheruthuruthy in Thrissur district lies the jewel of Kerala – Kerala Kalamandalam. Vanumati said – “It is the temple to every art lover of Kerala.” Kerala Kalamandalam, deemed to be University of Art and Culture by the Government of India, is a major centre for learning Indian performing arts, especially those that developed in the southern states of India, with the special emphasis on Kerala.

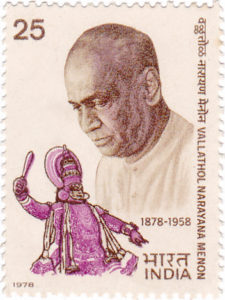

The inception of Kalamandalam gave a second life to three major classical dance performing arts of Kerala – Kathakalī , Kudiyattam and Mohiniyattam – by the turn of the 20th century, facing the threat of extinction under various regulations of the colonial authorities. It was at this juncture, in 1927, that Vallathol Narayana Menon and Mukunda Raja came forward and formed a society called Kerala Kalamandalam. They solicited donations from the public and conducted a lottery in order to raise funds for this society.

The inception of Kalamandalam gave a second life to three major classical dance performing arts of Kerala – Kathakalī , Kudiyattam and Mohiniyattam – by the turn of the 20th century, facing the threat of extinction under various regulations of the colonial authorities. It was at this juncture, in 1927, that Vallathol Narayana Menon and Mukunda Raja came forward and formed a society called Kerala Kalamandalam. They solicited donations from the public and conducted a lottery in order to raise funds for this society.

Vallathol Narayana Menon (16 October 1878 – 13 March 1958) was a poet in the Malayalam language, which is spoken in the south Indian state of Kerala. He was one of the triumvirate poets of modern Malayala. The honorable Mahakavi (English: “great poet”) was applied to him in 1913 after the publication of his Mahakavya Chitrayogam. He was a nationalist poet and wrote a series of poems on various aspects of the Indian freedom movement. He also wrote against caste restriction, tyrannies and orthodoxies. He founded the Kerala Kalamandalam and is credited with revitalising the traditional Keralite dance form known as Kathakalī.

Kathakalī’s roots are unclear. The fully developed style of Kathakalī originated around the 17th century, but its roots are in the temple and folk arts (such as Kutiyattam and religious drama of the southwestern Indian peninsula), which are traceable back to the 1st millennium CE. A Kathakali performance, like all classical dance arts of India, synthesizes music, vocal performers, choreography and hand & facial gestures together to express ideas. However, Kathakali differs in that it also incorporates movements from ancient Indian martial arts and athletic traditions of South India. Kathakali also differs in the structure and details of its art form developed in the courts and theaters of Hindu principalities, unlike other classical Indian dances which primarily developed in Hindu temples and monastic schools.

The term Kathakali is derived from Katha, which means “story or a conversation, or a traditional tale”, and Kali, which means “performance and art”. The dance symbolizes the eternal fight between good and evil.

The term Kathakali is derived from Katha, which means “story or a conversation, or a traditional tale”, and Kali, which means “performance and art”. The dance symbolizes the eternal fight between good and evil.

Sunetra walked towards her cab, it’s time to witness Kalamandalam with her own eyes. It is going to be an hour drive to Kalamandalam from Athirapally waterfalls. After reaching there, Sunetra will look for Chinamma. Vanumati told, how she learnt everything from Chinamma. Chinamma was not only her Guru but a mother too. After her divorce, Vanumati had only one person beside her through thick and thin – it was Chinamma.

This is the beauty of art. It makes you responsible as well as sensitive at the same time.

The driver stopped the car near the front gate. Sunetra was awestruck. She couldn’t believe her eyes. Entering the gates of Kalamandalam, gave her all the joy she could imagine for. She took off her shoe on the stairs and walked towards the office room. A girl was standing near the office room door when Sunetra was enquiring about Chinamma. The girl came to Sunetra and with a smiling face told her – “Chinamma is having tea in the garden. Due to age issues she takes very few classes these days. Come with me. I will introduce you to her.”

Sunetra liked her. She was just like her few years back; flying around all over her dance school premises. Nodding with a smile Sunetra started walking with her.

They reached the backside of the university. There stood a little garden with a small table and two chairs in the middle facing the greenery of Kerala all around. That was the first time Sunetra saw Chinamma. She looked like that cuddly, loving grandmother who never gets tired of telling you stories.

They reached the backside of the university. There stood a little garden with a small table and two chairs in the middle facing the greenery of Kerala all around. That was the first time Sunetra saw Chinamma. She looked like that cuddly, loving grandmother who never gets tired of telling you stories.

“Chinamma! She was asking for you at the office room” – said the girl.

Chinamma gave her a nod and smiled. The girl smiled back and gestured Sunetra to take a seat and left.

Sunetra sat in front of Chinamma, she was just about to introduce herself…suddenly Chinamma took her hand and said – “How are you my dear? I hope you had no difficulties arriving here.”

Sunetra felt the warmth of motherly affection after a very long-time. Her mother passed away 7 years back so whatever is left is in her memory.

“I am so pleased to finally meet you Chinamma. I heard so much about you from Vanumati. But I want to know it all from you now. That is the reason, I have come all this way.” – her eyes were glowing in excitement.

Chinamma said – “Yes, Vanu have told me all. I heard you are collecting the history of Indian Classical Dances and you have come to me to know about Kathakali.”

Chinamma said – “Yes, Vanu have told me all. I heard you are collecting the history of Indian Classical Dances and you have come to me to know about Kathakali.”

As they started talking, a man came and served them an authentic welcome drink of Kerala – spiced Sambharam. This is one of the most old-fashioned drinks in this part of the world. It is just pure buttermilk, and seasoned with shallots, garlic, ginger, green chilli, yellow chilli, bilimbi (pulinji), asafoetida powder, coriander leaves, mint leaves, mango and pineapple slices. One of the main highlights of this drink is that it is sugarless, despite the mango and pineapple, so if you are watching those calories, this would be an ideal drink.

Sipping to cold Sambharam, Chinamma told Sunetra – “Elements and aspects of Kathakalī can be found in ancient Sanskrit texts such as the Natya Shastra. The kathakali is attributed to sage Bharata, and its first complete compilation is dated to between 200 BCE and 200 CE, but estimates vary between 500 BCE and 500 CE.”

The most studied version of the Natya Shastra text consists of about 6000 verses structured into 36 chapters. The text, states Natalia Lidova, describes the theory of Tāṇḍava dance (Shiva), the theory of rasa, of bhāva, expression, gestures, acting techniques, basic steps, standing postures – all of which are part of Indian classical dances including Kathakali. Dance and performance arts are a form of expression of spiritual ideas, virtues and the essence of the scriptures.

Theme:

Theme:

Kathakalī is structured around plays called Attakatha (literally, “enacted story”, written in Sanskritized Malayalam. These plays are written in a particular format that helps identify the “action” and the “dialogue” parts of the performance. The Shloka part is the metrical verse, written in third person – often entirely in Sanskrit – describing the action part of the choreography. The Pada part contains the dialogue part. These Attakatha texts grant considerable flexibility to the actors to improvise. Historically, all these plays were derived from Hindu texts such as the Ramayana, the Mahabharata and the Bhagavata Purana.

A Kathakalī repertoire is an operatic performance where an ancient story is playfully dramatized. Traditionally, a Kathakali performance is long, starting at dusk and continuing through dawn, with interludes and breaks for the performers and audience. Some plays continued over several nights, starting at dusk every day. Modern performances are shorter. The stage with seating typically in open grounds outside a temple, but in some places, special theatres called Kuttampalam built inside the temple compounds have been in use.

Performance:

Performance:

The stage is mostly bare, or with a few drama-related items. One item, called a Kalivilakku (kali meaning dance; vilakku meaning lamp), can be traced back to Kutiyattam. In both traditions, the performance happens in the front of a huge Kalivilakku with its thick wick sunk in coconut oil, burning with a yellow light. Traditionally, before the advent of electricity, this special large lamp provided light during the night. As the play progressed, the actor-dancers would gather around this lamp so that the audience could see what they are expressing.

The performance involves actor-dancers in the front, supported by musicians in the background stage on right (audience’s left) and with vocalists in the front of the stage (historically so they could be heard by the audience before the age of microphone and speakers). Typically, all roles are played by male actor-dancers, though in modern performances, women have been welcomed into the Kathakali tradition.

The two very important aspect of Kathakali is the costume and the presentation in which music plays a key role.

The makeup follows an accepted code, that helps the audience easily identify the archetypal characters such as gods, goddesses, demons, demonesses, saints, animals and characters of a story. Seven basic makeup types are used in Kathakali, namely Pachcha (green), Pazhuppu (ripe), Kathi (knife), Kari, Thaadi, Minukku and Teppu. These vary with the styles and the predominant colours made from rice paste and vegetable colours that are applied on the face. Pachcha (green) with lips painted brilliant coral red portrays noble characters and sages such as Krishna, Vishnu, Rama, Shiva, Surya, Yudhishthira, Arjuna, Nala and philosopher-kings.

The character types reflect the Guṇa theory of personalities in the ancient Sankhya school of Hindu philosophy. There are three Guṇas, according to this philosophy, that have always been and continue to be present in all things and beings in the world. These three Guṇas are sattva (goodness, constructive, harmonious, virtuous), rajas (passion, aimless action, dynamic, egoistic), and tamas (darkness, destructive, chaotic, viciousness). All of these three gunas (good, evil, active) are present in everyone and everything, it is the proportion that is different, according to the Hindu worldview. The interplay of these gunas defines the character of someone or something, and the costumes and face colouring in Kathakali often combines the various colour codes to give complexity and depth to the actor-dancers.

Like many classical Indian arts, Kathakali is choreography as much as it is acting. It is said to be one of the most difficult styles to execute on stage, with young artists preparing for their roles for several years before they get a chance to do it on stage. The actors speak a “sign language”, where the word part of the character’s dialogue is expressed through “hand signs (mudras)”, while emotions and moods are expressed through “facial and eye” movements. In parallel, vocalists in the background sing rhythmically the play, matching the beats of the orchestra playing, thus unifying the ensemble into a resonant oneness.

Like many classical Indian arts, Kathakali is choreography as much as it is acting. It is said to be one of the most difficult styles to execute on stage, with young artists preparing for their roles for several years before they get a chance to do it on stage. The actors speak a “sign language”, where the word part of the character’s dialogue is expressed through “hand signs (mudras)”, while emotions and moods are expressed through “facial and eye” movements. In parallel, vocalists in the background sing rhythmically the play, matching the beats of the orchestra playing, thus unifying the ensemble into a resonant oneness.

A Kathakalī performance typically starts with artists tuning their instruments and warming up with beats, signalling to the arriving audience that the artists are getting ready and the preparations are on. The repertoire includes a series of performances. First comes the Totayam and Puruppatu performances, which are preliminary ‘pure’ (abstract) dances that emphasize skill and pure motion. Totayam is performed behind a curtain and without all the costumes, while Puruppatu is performed without the curtain and in full costumes.

Chinamma’s stories was creating vision in Sunetra’s eyes. She could see the preparations and every other little detail in her imagination. Chinamma talked about her Guru Vasu Pisharody. After an initial brief stint at Kerala Kalamandalam, Vasu Pisharody worked at a Kalari (Kathakali classroom) run by the Guruvayur Kathakali Club. He re-joined Kalamandalam in 1979 and worked there for two decades before retiring as its vice-principal in 1999. Vasu Pisharody is a winner of the prestigious Central Sangeet Natak Akademi award. A frontline disciple of Padma Shri Vazhenkada Kunchu Nair, he excels in virtuous pachcha, anti-hero Kathi and the semi-realistic minukku roles alike. Nalan, Bahukan, Arjunan, Bhiman, Dharmaputrar, Rugmangadan, Narakaasuran, Ravanan, Parashuraman and Brahmanan are his masterpieces.

Our country is much enriched with art and culture. As an Indian Sunetra felt so proud that she was facing scarcity of word to explain her emotions. Also sitting in front of Chinamma, considered to be an idol to all, Sunetra thanked Vanumati in her heart for gifting her the opportunity to meet her.

What Chinamma said next surprised Sunetra to the core. “People often think Westernise culture has redefined our Indian ideologies but very few of them know that there are international dance forms which are considered as disciples of Kathakali.” – said Chinamma.

“Really! What are those?” – asked Sunetra.

Kathakalī-style, costume rich, musical drama are found in other cultures. For example, the Japanese Noh (能) integrates masks, costumes and various props in a dance-based performance, requiring highly trained actors and musicians. Emotions are primarily conveyed by stylized gestures while the costumes communicate the nature of the characters in a Noh performance, as in Kathakali. In both, costumed men have traditionally performed all the roles including those of women in the play. The training regimen and initiation of the dance-actors in both cultures have many similarities.

Noh is often based on tales from traditional literature with a supernatural being transformed into human form as a hero narrating a story. Noh integrates masks, costumes and various props in a dance-based performance, requiring highly trained actors and musicians. Emotions are primarily conveyed by stylized conventional gestures while the iconic masks represent the roles such as ghosts, women, children, and the elderly.

Also, there is another dance form named Jīngjù, a Chinese art of dance-acting (zuo), like Kathakali presents artists with elaborate masks, costumes and colourfully painted faces. Jīngjù (another name Peking Opera) features four main role types, sheng (gentlemen), dan (women), jing (rough men), and chou (clowns). Performing troupes often have several of each variety, as well as numerous secondary and tertiary performers. With their elaborate and colourful costumes, performers are the only focal points on Peking opera’s characteristically sparse stage. They use the skills of speech, song, dance and combat in movements that are symbolic and suggestive, rather than realistic. Above all else, the skill of performers is evaluated according to the beauty of their movements. Performers also adhere to a variety of stylistic conventions that help audiences navigate the plot of the production.

“As the roots of Kathakali couldn’t be traced due to its ancient existence, some people raise questions about this dance form being classical. What would you say about that Chinamma?” – asked Sunetra.

“If we look at our benchmarks to see if it is classical, it only scores modestly. It is definitely old, but this is one of the least important of the criteria. It is not necessarily something that upper classes use to define their identity; indeed, the opposite is probably true. Its most glaring deficiency is seen in its inability to transcend its attachments to the Keralite community. The average Indian (non-Malayali) has only a vague knowledge that it exists and will live their entire life without ever even seeing a Kathakali performance. Therefore, from a sociological standpoint it is probably more correct to call Kathakali “traditional” instead of classical.” – said Chinamma with a peaceful smile on her face.

“My students are going to perform a piece of Mahabharata in the evening. Why not you come and witness this glorious dance form by yourself?” – Chinamma told Sunetra.

Sunetra was on cloud nine. There’s nothing more she could’ve asked for. She touched Chinamma’s feet to pay her regards and nodded with excitement. Before she leaves for Tamil Nadu for her next adventures; this is probably the best present she can take from Kerala. A present that will stay with her till eternity.