Advent of narrative folk art of Bengal

(Weaving stories through colours – tribes painting)

(Reading Time: 20 min Approx)

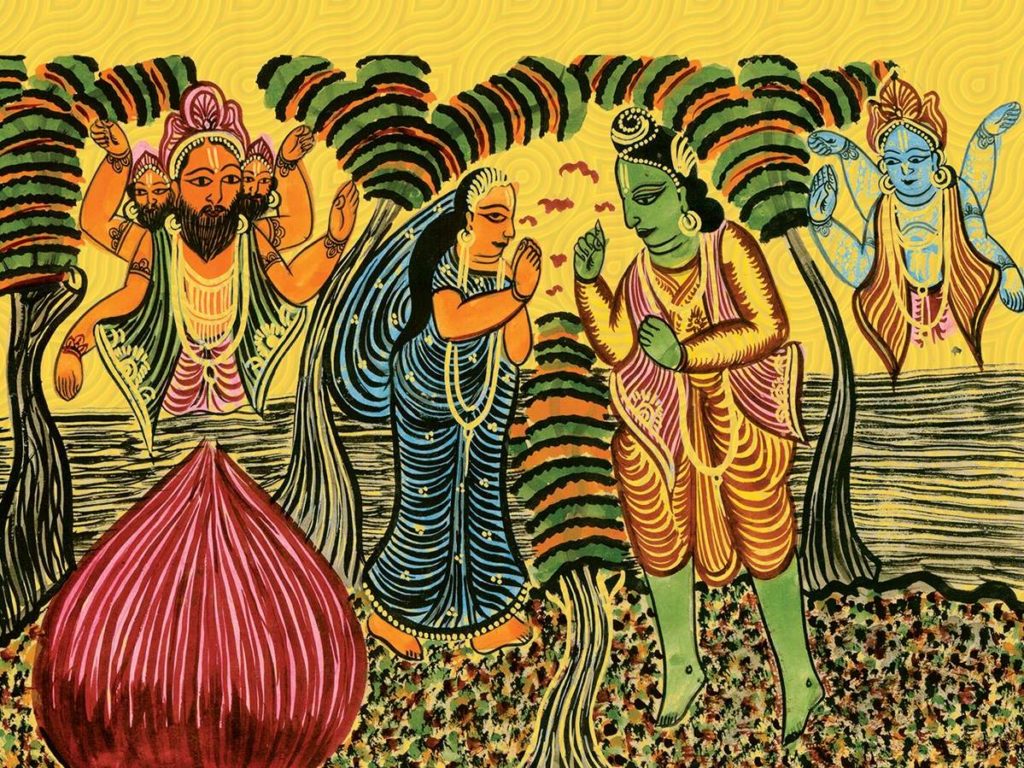

The Patachitra is a performing art that was initiated in Eastern India i.e. Early Bengal, Odisha and parts of Jharkhand and Bihar. It does not belong exclusively to one region. They came to being as an expression of creativity among the rural inhabitants of the aforementioned places, we can call them tribes painting as well. They cannot be examined only by their temporal or spatial aspects but also their mode of expression, the root of these art forms. The folk arts were transmitted from generation to generation; they were not just means of livelihood, they were a way of living, an act of devotion.

Paṭachitra has been one of the most researched, most appreciated visual arts. And like many popular folk arts there have been many doubts and misconceptions regarding Paṭachitra. The Paṭachitra of these places i.e. Bengal, Odisha, parts of Bihar and Jharkhand came to existence at different times however not too far apart. The method of the painting or the mediums maybe the same but there are certain stylistic differences among them owing to the regional variations and the historical aspects that went into making each one of them unique and original in their respective ways.

This essay attempts to look in to the Paṭachitra traditions of Bengal by briefly delineating the origin, process, stylistic features, and the ways through which the patuas reflected oral traditions, mythology, folktales in their creative mediums.

Patachitra (tribes painting)

Early Paṭachitra tradition can be broadly categorized into two types:

- Bengal Patachitra

- Odisha Pattachitra

In Sanskrit, the word ‘paṭa’ means cloth and ‘chitra’ means picture. Paṭachitra or Pattachitra is a panoramic term for cloth painting, scroll painting, painting on palm leaves (Tala Paṭachitra), and painting on ṣarās that were made from soil and on many more types of surfaces. Paṭachitra is perhaps the most ancient art form in Eastern India that emerged back in the early 2nd century or the Pre-Pala period.

Origin of the Bengal Paṭachitra – tribes painting.

Bengal Paṭachitra is one of the intangible cultural heritages of West Bengal. There are some academic debates on the timeline of its origin. It has been referred to in the Buddhist literature in 1st century A.D., in Haribansha in 2nd century, in Abhiyanashakuntalam and Malavikagnimitra in 4th century and in Harshacharita in 7thcentury.

Paṭachitra in Bengal was practiced in some specific regions of Birbhum, Bankura, Purulia, Hooghly, 24 Parganas and West Medinipur districts. More than just painters, patuas are also lyricists, singers, performers and true artists. It was not just a form of painting. It was a family practice of oral and visual narration and storytelling. The content of these paintings comprised of the three important literary works about Bengal as a region- Mangal Kavyas (Benediction Poems): Chandi Mangal, Manasa Mangal and Dharma Mangal. These poems were visually portrayed in the scrolls and the Patuas who painted them and visited neighboring villages and narrated the Kavyas in public places.

The Bengal Paṭachitra has also evolved into several aspects such as:

- Durga Pat

- Chalchitra

- Medinipur Paṭachitra

- Kalighat Pat

Process, stylistic features and themes of Bengal Patachitra

Since Patachitra was a family tradition at its time of birth, almost all the members of the family were involved in the process. The responsibilities were divided into preparing the glue, the canvas, applying colors and give the final lacquer coating. The principle chitrakār drew the initial outline and gave the final finishing.

Paintings were done on cotton canvas strips and scrolls. The canvas was prepared by coating the cloth with a mixture of chalk and gum which gives the cloth a smooth leather finish. First the artists draw a fine outline with lamp soot. Natural dyes were then filled within the outlines. Due to these vegetable dyes, the paintings got a certain brightness and longevity. The final outline was drawn with finely sharpened charcoal pencils. Often the paintings were also done on several equal sized palm leaves and were sewn together like a book. The average length of the scroll paintings varies between 4 and 20 feet.

All colors that were used in the painting of the scrolls were natural- chalk dust, turmeric paste, vermillion or mete sindur (red-colored soil), vegetable dyes, soot, mud and cultivated indigo. The lines are distinctly bold, swiftly drawn with beautiful precision. The dignified attitude and novelty of form of the figures reveal the exceptional talent of the artists. A scroll patachitra is divided into vertical compartments of varying sizes and each block comprises of a distinct episode of the story being narrated. These scrolls can also be folded up and hence called ‘Jorano pat’.

There are many themes that are encapsulated within the Patachitra tradition. The principle thematic contents that were and still used are the Mangal Kavyas, Ramayana, Mahabharata and the indigenous folktales of Bengal about Behula, Lakkhindar, and Chandi being the most popular. The Mangal Kavyas consist of religious compositions and narrations representing regional deities, entangled with the socio-cultural scenario of the then rural Bengal. The narratives were usually written in the form of verses. The verses also comprised of tales regarding navigation, maritime warfare, sea and river voyages and trade along the ancient seaport of Tamralipta.

In the earlier times during the festive season, the patuas would travel from village to village, with their portable scrolls. In front of a suitable gathering, they would unfold the long scrolls, frame by frame, and narrate the stories painted on them. In ancient times, tales from religious texts, epic poems and mythologies, formed the bulk of the narratives. Every pata had a song related to it and was sung by the paṭua at the places he went to. The practice of singing along with the scrolls in villages was called Paṭua Sangeet. The poems or songs related to the respective scrolls were narrated or sung in the villages of Naya, Birbhum, Jhargram, Bankura, Medinipur, 24 Parganas by the paṭua and their family members. The rural people gathered around to hear it and would pay money which was the source of livelihood of the paṭua family. Currently, the chitrakars draw upon contemporary events too to popularize their repertoire.

Not only as traditional painters or narrators of tales, these patua or chitrakar have a unique identity too that speak volumes about India’s religious tolerance. A religious syncretism can be observed in the Patachitra tradition. Hindu as well as Muslim families were involved in this process. Despite their religion, they were well-versed in Hindu mythology. In fact, during Hindu religious or social functions, they would be invited to perform.

Jādu Paṭuās

Ajitcoomar Mukherjee described the lives of the Jādu Paṭuas, another section of Paṭuas. They resided in villages of Bankura, Birbhum, tribal regions of early Bengal. These patuas also drew miniature paintings that were made on ‘tulat paper’ (hand-made coarse paper). The stylistic features of these miniature scrolls were quite similar to the mural paintings. These patuas were known as Jādu Patuas. They narrated stories about daily happenings in the lives of rural people that were related to the paintings on these miniature scrolls. They were direct in story-telling power and the interpretations were left up to the audience. From the writings of Mr. Gurusaday Dutt, we come to know that Jādu Patuas also frequented the villages where Santhal and the Bediya tribes resided. These Jādu patuas seldom lived in their homes. They roamed in groups and visited villages to practice their storytelling through art to earn money. Whenever they came to know that a member of a family had passed away among the Santhals or the Bediyas, the paṭua would arrive at the house of the bereaved family with a sketch of the deceased person drawn from his own imagination. There was no attempt at establishing similarities but merely a drawing of the deceased person- male, female or child. The Jādu paṭua presented the picture to the family only leaving the iris of the eyes undrawn. He would show the sketch to the family and tell them that the soul of that person was wandering blindly in the spiritual realm and will continue to do so unless his/her family sends gifts or money through the paṭua so that he can perform the Chakshudān (bestowal of eye sight). The family members would give him alms and the paṭua would give the finishing touch to the sketch by drawing the iris of the eye thus signifying that the soul was no longer blind in the other world. Some of these miniature paintings were reproduced and can be found in the temples of Bankura in Western Bengal.

Current Initiatives

Due to the popularity of modern forms of entertainment, this vintage practice is suffering a threat of oblivion. The rising prices is also forcing the artists to abandon their use of the traditional dyes in favor of synthetic colours. Many, especially from the younger generation, began to migrate to more paying professions. Those who continued in the family profession began selling the pata as a decorative item. There were sporadic attempts by welfare organizations to employ these people during campaigns involving nature conservation, health and hygiene, anti-superstition, etc.

Even though the popularity of this unique art has suffered major setbacks, it is one of those few handicrafts of West Bengal that are still surviving the ravages of the contemporary times. Many-a-times, the paintings are done on paper, instead of a thick cloth. The themes of paintings have also changed with time. New themes have been incorporated within the Patachitra tradition, to cater to the taste of their contemporary audience. Often it is glued to a saree for ease of unraveling and storing. In the current times patua painters of Bengal are also initiating to decorate handicrafts, household items and textiles for sustaining a living. Many patua painters have also now taken to painting only, rather than storytelling through singing, in an effort to sustain themselves economically.

In a village in West Midnapore district in West Bengal, approximately 250 patuas are striving to keep this intangible heritage alive. Even as performing arts and folk traditions remain invaluable intangible cultural heritage of communities all across, many are diminishing owing to rapid changes in the socio-cultural fabric of the world. Safeguarding efforts by local governments, international bodies such as UNESCO and various non-governmental organisations can go a long way in keeping alive traditions through time.

Writer Mehk Chakraborty wrote in an article published in Media India Group that ‘the patua community in West Bengal has come under such initiatives by the Government of West Bengal. Projects like Ethnomagic Going Global a few years ago and the government’s push to gain Geographical Indication tag for many rural crafts and arts, including patachitra paintings, gives hope to keep this lively folk tradition alive.’

Writer Uttara Gangopadhayay documented in the Outlook Traveller the following- ‘the art got a fresh lease of life when the Government of West Bengal’s Department of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises & Textiles, in association with UNESCO, decided to develop a Rural Craft Hub in Pingla in Midnapur. Spearheaded by a social enterprise called Banglanatak the artists of Pingla not only began to use traditional dyes but also learned how to market their products as well as use their traditional art in other mediums. Naya village of Pingla developed into an artists’ village where the NGO Banglanatok held its first annual craft fair called Pot Maya in 2010. Usually held in winter, the three-day fair is one of the best times to visit the village. Artists turn their courtyards and verandas into sales counters. The itinerant artists give impromptu performances with their jorano pata. Apart from traditional square patas or jorano pata, you will find the art form being used to decorate tee-shirts, caps, umbrellas, bags, lampshades, saris and shawls, book covers, kettles and tea pots, etc. You may also attend workshops to learn how to prepare natural dyes and the traditional style or technique of painting.’

Patachitra was and still is a fluid form of art and as said before one of the most important intangible heritages. Like all vernacular arts this versatile art tradition too was conceptualized and with time migrated and evolved into several offshoots that permeated the boundaries of regions and states.

The Patachitra tradition is not just about the patuas and their painted scrolls; it is a dynamic practice which remains the vessel for the folk tales and mythological stories that form the crux of the ancient and indigenous Bengali literary and social heritage.

References

- Myths and Folktales in the Patachitra Art of Bengal: Tradition and Modernity, Bajpai, Lopamudra Maitri, ‘Visual Culture in the Indian Subcontinent’, Publ. by Chitrolekha International Magazine on Art and Design, 2015.

- The Folks Arts of Bengal and Evolving Perspectives of Nationalism, 1920s-40s: A Study of the Writings of Gurusaday Dutt, Basu, Rituparna and Basu, Rituparva, Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, Vol. 70 (2009- 10), Publ. by The Indian History Congress.

- Folk Art of Bengal, Mookerjee, Ajitcoomar, Publ. by the University of Calcutta, 1939.

- The Patas and Patuas of Bengal, Ray, Niharranjan, Publ. by Indian Publications, Calcutta, 1973.

- Bengal’s ‘Pat’ of Gold: An exposition of contemporary and heritage scroll paintings, Collection of Essays curated by Kolkata Centre of Creativity and The Crafts Council of West Bengal, Published by Emami Art, 2018.