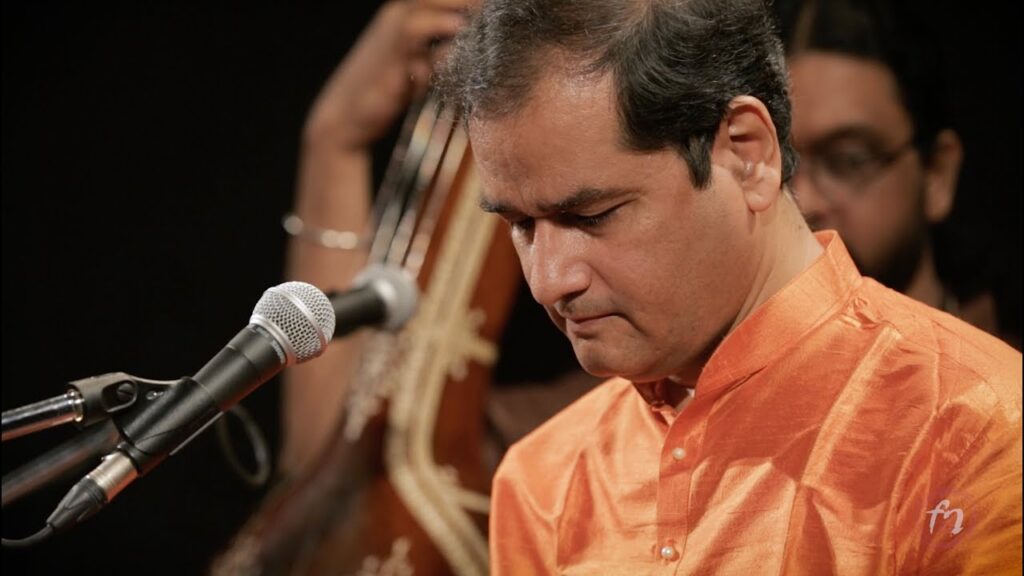

PANDIT UDAY BHAWALKAR…in dialogue with…SUBHADRAKALYAN

— Reading Time: 20 Min Approx

THE MAN, THE PROPHET

The previous segment was about the art of singing Dhrupad and how Uday Dada interprets it. This is the last segment where we will discuss in detail about his career simultaneously exploring him as a most extraordinary human being he actually is.

When did you start your career as a full-fledged performer?

As I told you before, my first concert was in 1985, when the Gurukul in Bhopal showcased us as the young talents. The event was named, ‘Uttaradhikaar.’ After that I sang in the Dhrupad Festival in Bhopal in 1987. In 1989, I sang at the Tansen Samaroh in Gwalior. From 1990, I started performing for the SpicMacay concert series. The year 1996 was quite important for me, because I got a break to perform at the Hariballabh Sangeet Sammelan. The subsequent year, 1997, I performed at the Sawai Gandharv Music Festival. The same year I performed at the Shriram Shankarlal Festival.

Learning and performing would go on simultaneously. In 1990, I accompanied Bade Ustad to France and Holland. The director of the Rotterdam Conservatorium, a world music school in Amsterdam, requested me to teach there. I stayed there for eight months and returned. They wanted I stayed there for some time longer, so I again went there and stayed there for another eight months and taught them. But then I left the job.

Your first performance was in 1985 when you were a student. And now you are performing when you are a Guru. What kind of transformation have you gone through? How would you comment on the evolution that happened?

The art of what you are practicing and you, both go through a transformation when you immerse yourself into that. Thinking over it for long enough helps you to evolve in it.

One very important thing that helped me to evolve is that my joining ITC Sangeet Research Academy as a Guru. Here I got to mix with many other people who are actively practicing and teaching music of different genres. Exchanging ideas is a great thing that has helped me to improve. Earlier, there wasn’t any particular motto in front of me or my students. Here, the institution organizes gradation tests and recitals for the students which are making them to think about music and learn music with a definite aim. The students also get to know the opinions of the other senior musicians and learn a thing or two from them. Even I get to learn a lot from my association with the other musicians that I have had having come here. All this is helping me to grow. Again, I always tend to see my own reflection in my students. That’s important for a teacher at times. That helps me to evolve as well.

Tell us about your own compositions.

It has been thirty years since I have started to compose. I have almost eighty compositions of my own. Sometimes I write the lyrics on my own and set the tune. Sometimes I get available lyrics and set the tune. Sometimes I even modify the traditional compositions so that they fit to the time and sound appropriate. I started to compose when I got to know some new raga but didn’t learn the composition of it from Ustad. When I explored the ragas such as Dhani or Gawati, which are not usually sung in Dhrupad, I made my own compositions and added the ragas in the repertoire of Dhrupad. I composed my first Bandish sometime during the mid 1980s. It was in the raga, Sohini – Awan Ke Gaye.

One thing I want to say from my perspective as a teacher. I believe, no man is completely perfect. And in case of art, there is no such thing called perfection. And there shouldn’t be actual perfection in art. Art should flow on its own. One practicing art must find newness in every aspect of the art one is practicing. It should be a neverending process. That’s only how art lives. One should never forget to feel the newness of the same thing one has practiced several times.

One must know about one’s limitations, and one must get over them. I am always aware of where I am limited. I try to find out what could be the thing that I am not getting at. To solve this out, I have designed vocal exercises which I add to what I learnt from my Ustad. I practice and teach what I have learnt from them, but I also try to inculcate my own vocal exercises into them. I somehow find the vocal exercises I designed helpful. I teach them to my students keeping in mind they must not face the limitation I have faced. I tell my students, what I could not achieve, but I show them the way to achieve it. I think it’s also necessary to know where you are unable to achieve a thing. Who knows, if I had gone thirty years back, I maybe could achieve it. This is actually what I believe is that, I was left to discover on my own. Ustad wanted me to find it out. I used my knowledge that I gathered from them, tried to carry it forward this way.

I intensely think on music. I even introspect on the various aspects of music, constantly thinking of what I have learnt and what it actually is. If I am singing some exercises, I think how they will improve my voice. If I am keeping the time in my hand, I think why this has been an age old tradition and followed by the artistes over generations. It’s only that I have to be conscious enough while singing. Being blind and just going by the process of rote learning doesn’t help. One has to think repetitively while practicing. Repetitive churning of the knowledge helps one to get at what could come out of it. With this, one must also be thoughtful about constant improvement. The moment one is satisfied with what one is doing, one meets with the end.

It’s not that there is a concrete answer whatever query that will arise from your thoughts, but the thoughts are surely not pointless thoughts. They help you to keep immersed into the subject which again will help in your delivery of your music. When I hear the masters singing, I find a uniqueness in every of their recitals. This comes from their thoughts, their application of their minds into what they are doing. One’s mind has to be connected to what one is doing. If one is playing the Tabla, one must not only play it with one’s hands. The mind has to be into it.

You have also sung in films like Aparna Sen’s Mr. and Mrs. Iyer or Mani Kaul’s The Cloud Door or Amol Palekar’s Anaahat. How would comment on the use of Dhrupad in films?

Mani Kaul himself was a disciple of the Dagar brothers. He was also a senior student of Ritwik Ghatak. He used to be influenced by Dhrupad. He believed, if one wants to learn the movements of the camera, one should learn it from the Alaap of Dhrupad. He would use the syllables of Alaap as an independent language for his films. He would design the order of the syllables and the movement of the tones in a way, a dialogue is delivered.

Amol Palekar’s Anaahat was set in the 10th century India. He wanted a very minimalistic soundscape for his film where he would just use the Tanpura, the Veena and the acoustic voice.

Ustad Zakir Hussain was the music director of Aparna Sen’s Mr. and Mrs. Iyer. Zakir Ji called me to come to the studio. I was suffering from high fever that day, but still I visited him at the studio. He asked me to sing the raga, Shree, according to the movement of a particular sequence. I sang it and they recorded it.

There are some people who look down upon film music and the practice of using classical music in films. Do you think application of classical music in films actually indicates at its dishonor?

I have respect and regards for the other genres of music as much respect and regard I bear for Dhrupad. Look, the form is not important. What instrument you are playing is not important as well. Neither is important what school you are following while playing. What is important is honesty. The most important thing is, whatever you are playing, it has to come out from your heart. Music must not be seen in such a demarcated manner but as a whole. Here is one other thing you must remember. There is no guarantee; you are going to play well at each and every concert when you are playing a classical recital or you are going to rock at each and every concert you are delivering a repertoire of popular music. This kind of a classification is simply baseless. Success in any kind of a field is not easy. It comes by several steps. And it’s always important as to how a person is thinking and subsequently executing his thoughts out. The medium he is choosing is not important. What is important is the content. If someone is not as good as expected at the basic fundamentals of music; even if he sings classical music; we cannot call it good music.

Remember one thing: never go by what other people. You will end up being frustrated. Instead, think this way: you life is like a mustard seed, but you should look at it in a way that it appears as huge as the sky to you.

We have now come to the end of this entire conversation. I shall conclude this with a question – how does it feel to be a greatly revered exponent as well as a Guru of Dhrupad?

I only wish that I am able to carry forward whatever I have learnt from my Guru, whatever I have learnt from others. Whatever one does, one must do it with full dedication and honesty. For me, Dhrupad is the way to divinity and truth. Practicing it feels like being connected with a never-ending supreme energy such as the sky or an ocean…it’s such a deep process. An artiste must not have preconceived ideas about music. One must embrace the new things and be enriched. I often wonder what made the great masters what they were. In that way, I constantly receive inspiration from their ways of interpreting music.

I want to say this: one must not be forced to do anything. There has to be a kind of blissfulness, a love in whatever one does. Those are the major fuels to life. No matter how much one succeeds in life, if one lacks joyance and happiness, one is finished.

He stopped…

Here we ended the conversation. At the end, I was left in awe with his philosophies. Let’s hope, his thoughts and teachings inspire the world and help people to with music as their companion. All I can say is that, I am more than fortunate to have been his student. Had I not been his student, maybe, life would seem meaningless!