Quarter of a Century

Reminiscences of Kolkata International Film Festival

By – S U J O Y S H O M E, Journalist & Film Historian

(Reading Time: 15 min Approx)

25 long years! But it seems only the other day! Kolkata International Film Festival has traversed a quarter of a century. Jaded with watching—and sometimes not watching—commercial and run-of-the-mill bioscope throughout the year, desperate film enthusiasts get an opportunity to immerse themselves in a plethora of socially-conscious, aesthetically gratifying films of various styles, moods and genres at the annual carnival of world cinema.

Music, painting, sculpture, literature or theatre, after getting recognized as an art medium, got mired in the cesspool of commercialism. In the case of cinema, it was just the reverse—the magic of an overwhelming presence on the big screen! ‘Business! Business! Cinema, thou have no art?’—pondering over it, many talented creative artists—after overcoming insurmountable hurdles and crossing uncharted difficult terrains with their life-draining effort—at last reached the pinnacle of artistic creation and the glory of recognition of the art medium. In the exulted podium of film appreciation, with a dream of building a bond between the spirit and thought of art filmmakers and film connoisseurs across the world, the international movie fest saw the light of day.

1932 – The first festival of world cinema was held in Venice, Italy. In 1935, in the capital of erstwhile Soviet Union, Moscow. In France, in 1946, in the carnival city of Cannes. In 1951, in Berlin, when Germany was asunder. The first International Film Festival of India (IFFI) was held in Bombay in 1952—the first of its kind in Asia—and subsequently taken to Madras, New Delhi, Calcutta and Trivandrum, under the aegis of the Government of India. Being the capital city, New Delhi had an edge over the other cities for hosting the festival frequently, despite the miserable standard and dismal presence of local spectators. After crossing several film-making cities of India, IFFI seldom reached Calcutta, the workplace of stalwarts like Satyajit Ray, Ritwik kumar Ghatak and Mrinal Sen. It was a rare windfall for the most enthusiastic audience of art film in India. So in 1995, with the far-reaching initiative of Government of West Bengal, Kolkata became the nerve center of India’s second international film festival.

Let us not forget that India’s film society movement first started in this metropolitan city in October 1947, after the end of British rule, when the fledgling new republic of India was only two months old. The pioneer of ‘Calcutta Film Society’, the creator of great literature based classic film ‘Pather Panchali’ (‘Song of the Little Road’), became an international icon of Indian art film. The maestro’s first global recognition came in Cannes Film Festival.

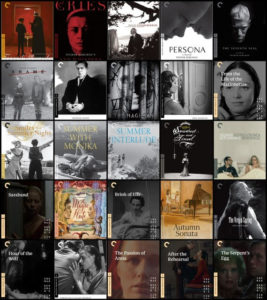

Three and half years after Satyajit Ray’s demise, the Kolkata International Film Festival (KIFF) was born. Without going abroad or to any other city of India, a home-grown academe of films flourished. The main venues of the festival—from Rabindra Sadan, Nandan 1-2-3-4, Paschimbanga Bangla Academy to Sisir Mancha, Kolkata Information Centre and Gaganendra Shilpa Pradarshanshala—virtually metamorphose into lyceums of film studies. Starting from cinema viewing, symposium, press conference, film-related exhibition or book and journal purchase and extending to discussion, argument and vibrant conversation, the festival has it all. Film theoreticians, critics, connoisseurs of cinema and movie buffs not only from Kolkata but from different parts of West Bengal and India interact with each other, as well as with foreign delegates and visitors and built lasting bonds of friendship. Whatever be the language of film dialogue, there is scope for exploring in cinema’s own language, the grammar, theme and experimentation of movies through debate and analysis. The joy of expressing appreciation for a film of one’s liking is incomparable. The thrill of these memorable 24 years lies in immersing oneself—diving innumerable times in the real and the surreal—in the artistic consciousness of immortal films of great creators of world cinema.

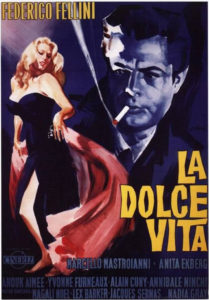

Federico Fellini’s ‘La Dolce Vita’ (‘The Sweet Life’) emphasizes the hedonism of contemporary Italian bourgeoisie through the ruthless probing viewpoint of paparazzi. The movie indulges in nudity, sexual jugglery, religious decadence and clash between prehistoric myth and postmodern morality. The opening scene of the film depicts the statue of Jesus Christ dangling from a helicopter.

Brutal simplicity is the fire of revenge—this theme shows the greatness and universality of the classical cinema of Turkish filmmaker Yilmaz Guney. His class-struggle-oriented thoughts and consciousness and depiction of unbearably suffocating indigenous reality are all inspired by political and socioeconomic mass movements. Through his personal experiences he had realized the despicable, volatile and desperate condition of his time and society, which he eventually portrayed with great artistic detachment in his films.

Polish filmmaker Andrzej Wajda’s antiwar trilogy underscores that violence begets violence and violence advances at its own pace until it destroys the killer. In the movie ‘Everything for Sale’ he wants to represent that instead of being confined to social responsibilities one has to be face-to-face with psychological reality. If one’s mind and body, character and intellect are afflicted by deadly disease, one has to face untimely demise, even before the fire of life is out—this is the message that drops like a pearl of wisdom from his lyric in celluloid ‘Sweet Rush.’

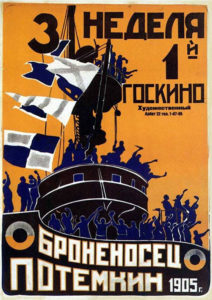

In Kolkata International Film Festival we had the opportunity to closely interact with Edwin Stanton Porter and David Wark Griffith, the original grammarians of cinema, and to take lessons on the philosophy of film form and film sense from Sergei Eisenstein. We watch Robert Flaherty’s classic ‘Nanook of the North’ and several creations of Joris Ivens, another magician of documentary film making.

The experience of Charlie Chaplin films is that of our happy childhood, adolescence, as well as melancholy, intellectual adulthood. When we went to see Jean Renoir’s ‘The River’, we suddenly remembered that this film was shot in Calcutta and its outskirts. That story was told by young Satyajit Ray, who witnessed the location hunting and shooting as a passionate film enthusiast.

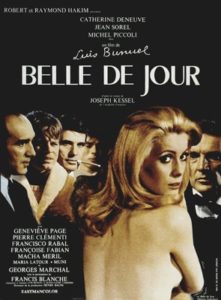

Pure and sacred as fire, Luis Bunuel strikes hard at religious beliefs in ‘Nazarin’ and his ‘Belle de Jour’ (‘Lady of the Night’) stands out as a masterpiece of unadulterated sexuality. Vittorio De Sica not only means a classic on the unemployed, helpless labourer and his little son like ‘Bicycle Thieves’, but also sociological fantasy like ‘Miracle in Milan’.

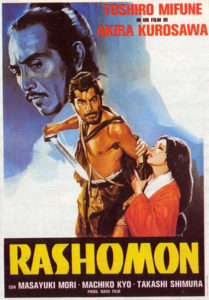

From ‘Rashomon’ to ‘Kagemusha’ (‘Shadow Warrior’) to ‘Madadayo’ (‘Not Yet’)—Akira Kurosawa’s philosophy of life and thought has taught us smouldering peace, passionate quest for truth, self-confident awareness of death, historical tradition, to name just a few!

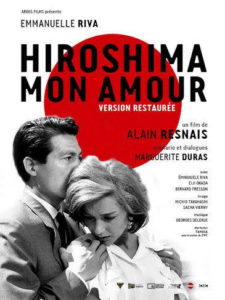

Style, variety of content and theme, psychological analysis, simplicity and honesty all combined together to make Michelangelo Antonioni’s art form very complex and inaccessible. Like our own Manik Bandyopadhyay in literature, Ingmar Bergman is our argumentative professor of sexual psychology in cinema. Despite the absence of rationale and sequence of events, the theme and presentation of Alain Resnais’s ‘Hiroshima Mon Amour’ (‘Hiroshima My Love’) intensely fascinate us even today.

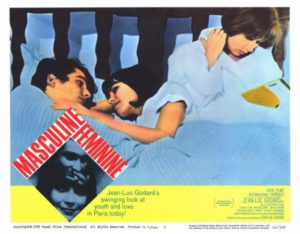

If one wants to appreciate the self-conflicted social philosopher Jean-Luc Godard’s search for beauty and truth and his dilemma between reality and illusion, one has to plunge into the inner depths and interiority of his films ‘Breathless’, ‘Masculin Feminin’ and ‘Weekend’. Francois Truffaut’s films have taught us the very essence of living—ease, grace, charm, attraction, wit, as well as empathy, modesty, self-effacement, frank expression of personal preference and elegance. We observe Andrei Tarkovsky’s surrealism in the visual images of memory and dream couched in the midst of exquisite beauty of nature.

In seminars and symposia, in press conferences and in the open premises of the KIFF there is ample scope for effortless interaction with world acclaimed filmmakers. Walking down the memory lane, I can call to mind my close encounter with two artists. In amiability of behavior, gracefulness of presence and eloquence of endless conversation, Polish filmmaker Krzysztof Zanussi reminds me of our Mrinal Sen. Contrary to his own cinematic characters’ reticence, Zanussi’s intellectual, witty and down-to-earth loquacity is very impressive and fascinating, ranging from politics to sociology, science to literature, ethics to poetic imagination and life experiences to eternal truth.

My old friend Anil Acharya, the editor of an intellectual Bengali magazine ‘Anushtup’, introduced me to his long-time friend Paul Cox. The excitement of our conversation started when Cox related the story of making his docufilm ‘Calcutta’ in the early 1970s. This Dutch-Australian creative artist, with his simplicity and intellect, threw an objective light on the people, politics, society, art and culture of Bengal. Our interaction reached his ‘Island’, a 1989 English-Greek film, which is the story of friendship of three women of different ages and from three different countries. What is unique about this movie is the graceful use of Bengali songs of Rabindranath Tagore, sung by our Ritu Guha in her spellbinding voice, at the beginning and end of the film.

Thus flowed our quarter of a century! Can such an academe of life and living ever die?

Well scripted and informative. A valuable writeup. Congratulations to the author, Mr. Sujoy Shome.

25 years of ‘Kolkata International Fil festival ?’ by WB govt. Information and cultural dept ? No – It was annual film festival of ‘Cine central’ – a calcuttan film society. Started by Sro Aloke chandra Chanda . Then Buddhadeb Bhattacharya CM/WB taken the event from the society. Its wrong infoemation that – 25 years of KIFF.